Okay – it’s official – I’m going to be difficult. I love Enceladus. Europa has been the astrobiology darling for a few years – but I think that Enceladus is now the forerunner.

It’s also where we should be looking next. Why you ask? Well here are a few reasons:

Enceladus (Saturn’s 6th largest moon) might be more easily explored than other promising sites in the outer solar system. Although Jupiter’s moon Europa may harbor a vast, briny ocean, it probably lies beneath an icy shell estimated to be up to 100km thick. And if Titan, contains liquid water, the reserves are probably well beneath its hydrocarbon-shrouded surface, which is cold enough to freeze even methane.

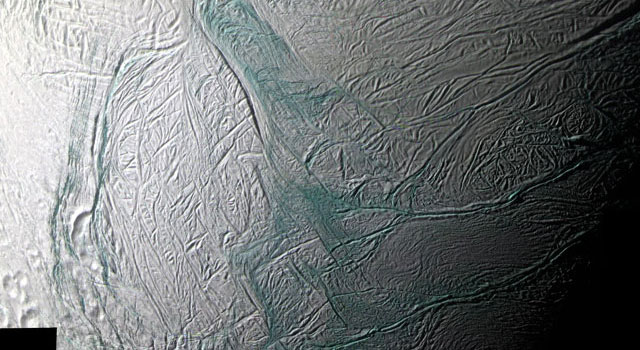

Enceladus’ surface courtesy of http://www.ciclops.org/

Enceladus has range of terrains from old, heavily cratered surfaces, tectonic features including scarps, troughs, grooves, ridges, and a young surface and evidence of recent tectonic activity in the southern hemisphere, less than 10 – 100 my. Plate movement is an indication of an active geology. A planet with an active geology may just harbour the right ingredients for life. The plume of water ice and other materials on Enceladus are known to erupt to a height of more than 80 km from the surface of the moon at temperatures of order 70 K to 150 K. This provides strong evidence that Enceladus’ interior may be warm, contain a sub surface ocean and that its surface is presently tectonically active.

In contrast to Europa, the exposed crevasses on Enceladus that may hold liquid water are thought to be only about a half-kilometer deep. The extent of Saturn’s E Ring indicates that the geysers on Enceladus have been expelling water for quite some time. Compared to Mars, Titan and Europa, Enceladus is the only other object in our solar system that appears to satisfy the conditions for maintaining life at present, even if the ability of life to evolve there is uncertain.

Enceladus surface features. Cr. NASA

Studies of Europa have concluded that it is extremely difficult to start or to sustain life in or on this moon. On Europa the proposed icy ocean is physically and chemically separated from heat, light, and non-water ice materials, imposing constraints on viability of chemoautolithotrophic life in their oceans. It’s unlikely that any subsurface ocean of Europa receives any sunlight to drive photosynthesis because they are far below the surface, the ice shell could be a few tens to hundreds of kilometers thick.

Life in Europa’s subsurface ocean would not only be difficult to create and/or sustain: it would also be extremely difficult to detect. The top ∼1 m of Europa’s ice is heavily bombarded by radiation and particles from the Jupiter’s magnetosphere, and therefore, is probably not representative of the composition of its interior.

Although it is possible that geophysical processes may permit materials from Europa’s ocean to reach its surface, it will be extremely difficult to discover whether life forms exist on Europa as it’s likely that whatever craft is sent, it will not only have to get to the moon (through Jupiter’s radiation) but send a lander and/or probe to the surface.

These would be used to probe through the ice crust and sample any liquid beneath, to determine amongst other things, the temperature, pH levels etc. A major problem would be to avoid contamination of the Europan environment.

Should a future mission be approved for Enceladus, it could conceivably fly through or land near the plume and possibly return plume material to Earth for laboratory analysis. Enceladus’ sub-surface ocean (if any) could be determined by examining the plume, without the risk of contamination.

Although the ESA’s JUICE (Jupiters’ Icy Moon Explorer), is planned to launch in 2022, beating out funding for the Titan Saturn System Mission, I’m hopeful that someone out there right now is planning a new mission to Enceladus.

Sharon

This article originally appeared in Astro Space News – you can find it here.